Joy may not be the first word that springs to mind when Westerners think about electrical power, but gorudubu (“joy” in the Bariba language) describes the feelings of the 40,000 adults and children benefiting from a new solar energy project in the rural and largely off-grid Kalalé District of Benin in West Africa. Over 5,000 families will achieve better health, thanks to an installation completed by the Washington, D.C. based nonprofit Solar Electric Light Fund (SELF).

“As a society, we don’t often think about lack of electricity as an underlying cause of health disparities,” says Robert Freling, SELF’s executive director. “You can provide all the vaccines in the world, but if a clinic doesn’t have the ability to refrigerate them, it doesn’t matter. Electricity is a prerequisite for healthy communities.”

The United Nations has seventeen Sustainable Development Goals, including “good health and wellbeing” (SDG 3) and “achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water” (SDG 6). In Benin, the lack of both energy and clean water means that vaccine-preventable waterborne diseases such as cholera, hepatitis A, polio and typhoid, are hard to fight. No electricity means no refrigeration; no refrigeration means limited vaccine storage. Limited vaccines result in these avoidable illnesses (plus dysentery), which remain a leading cause of death in Benin.

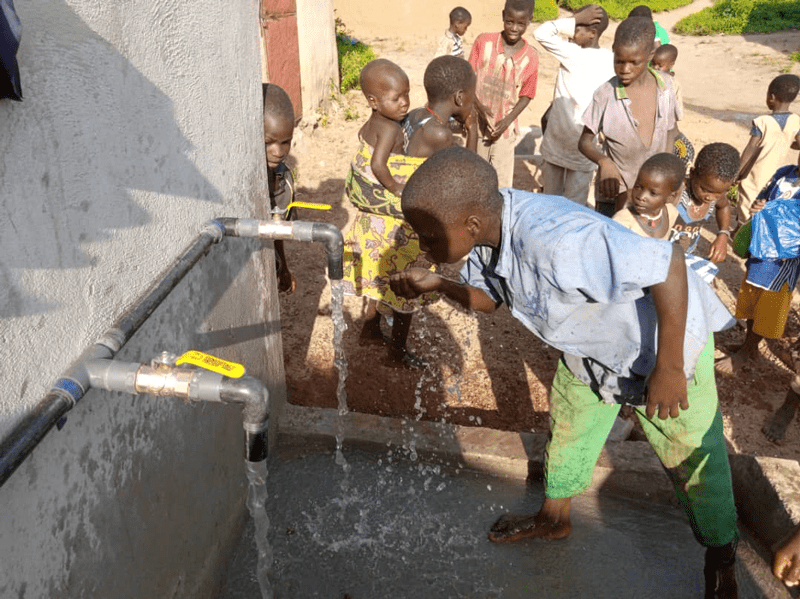

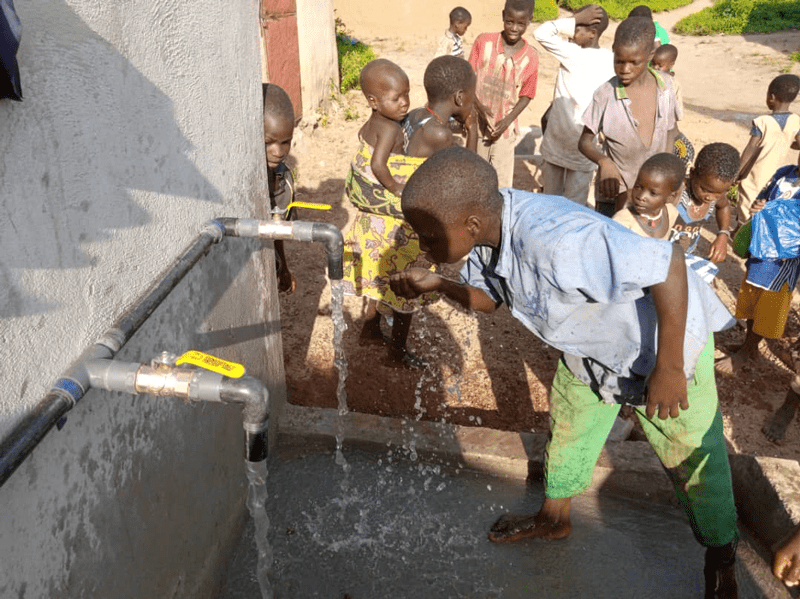

A recently completed solar energy project will disrupt this cycle and improve the health of the 40,000 people living in Kalalé District, which is approximately 325 miles (or a nine-hour drive) north of the capital, Porto-Novo. The SELF project had two solar energy components: Solar-driven pumps to fill 24 newly-constructed clean water reservoirs, and solar powered vaccine refrigerators in five area health clinics.

“Water access meets many fundamental needs, of course,” says Dr. Cardinal Akpakpa, a physician in the Kalalé District village of Gberougbassi. “Reliable access to clean water will not only improve hygiene measures, but it is also critical for the prevention of waterborne diseases.”

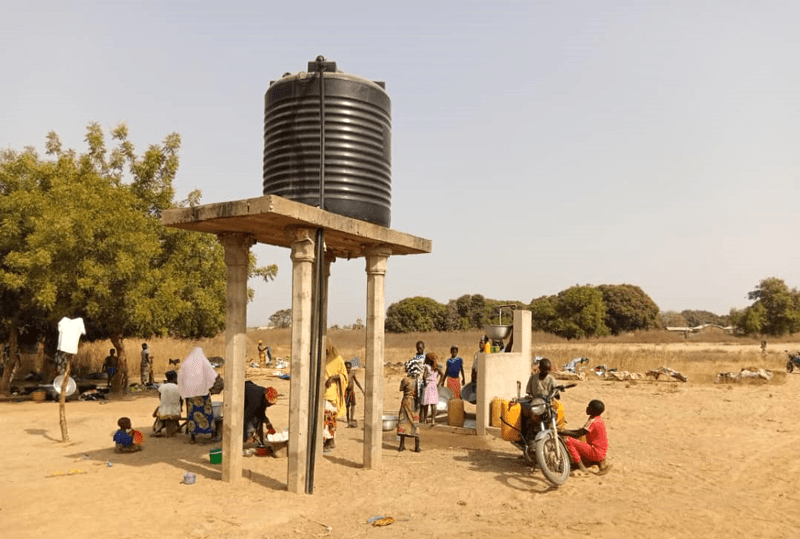

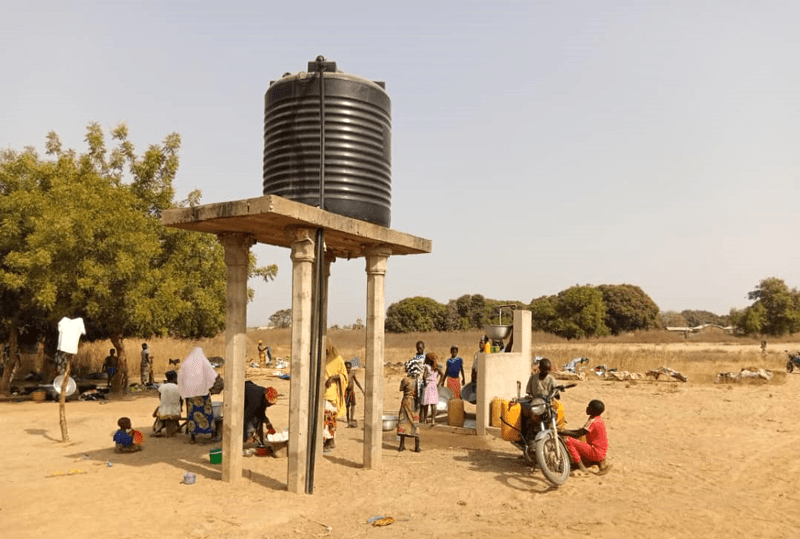

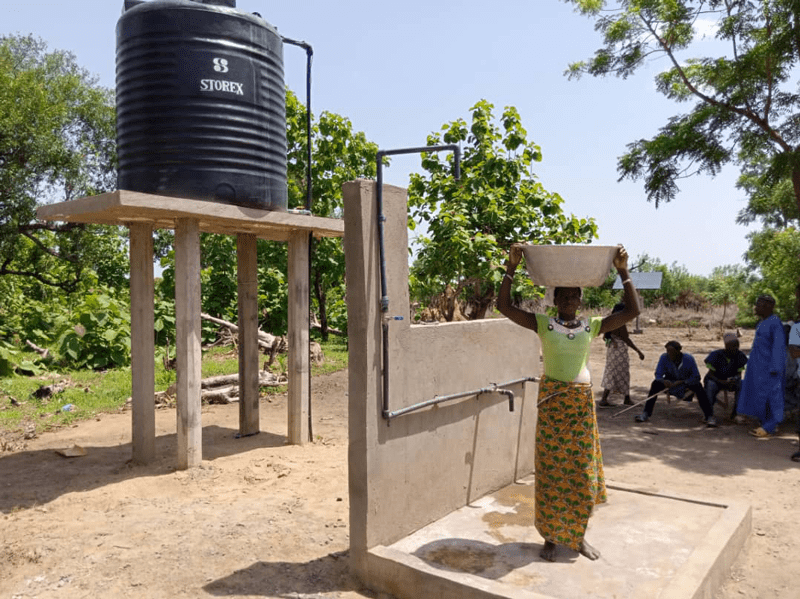

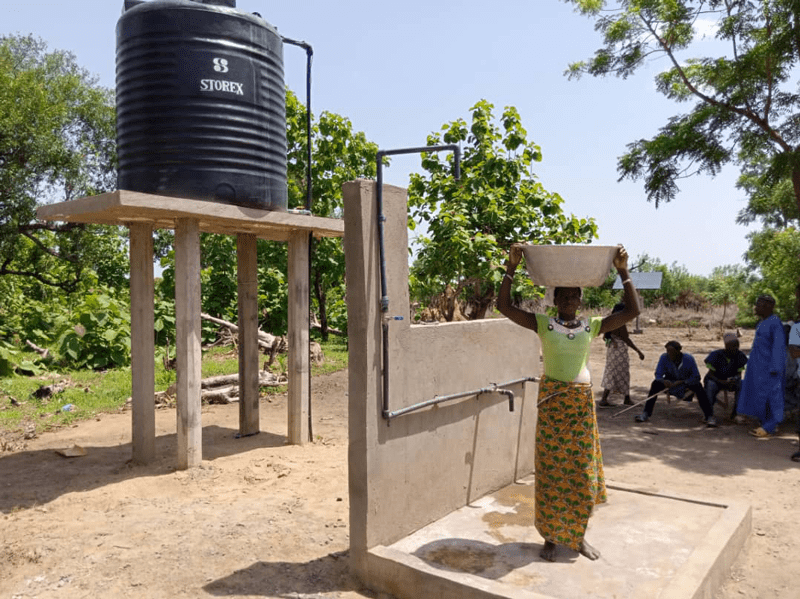

Many residents of Kalalé District used to scoop water from ponds or swamps located miles from their homes every single day. Others gathered water from shallow hand-pumped wells. Procuring and carrying water took hours of labor. Now, the residents walk much shorter distances to fill their water containers from the SELF water stations. Each of the 24 water stations has an elevated 5,000-liter storage tank that is filled by a solar-powered pump connected to an aquifer deep below. The water is not purified, but the sources themselves were tested and deemed suitable for human consumption. The water is not free; a small fee covers the cost of water station maintenance and the salary of the station attendant who is responsible for the security and operations of the facility.

An estimated 238 families, representing about 1,600 people, will use each water station. There is no set limit on the amount of water each family can buy and carry home. In practical terms, a typical family of six will use the equivalent of one American bathtub full of water to meet their daily hydration, cooking and cleaning needs.

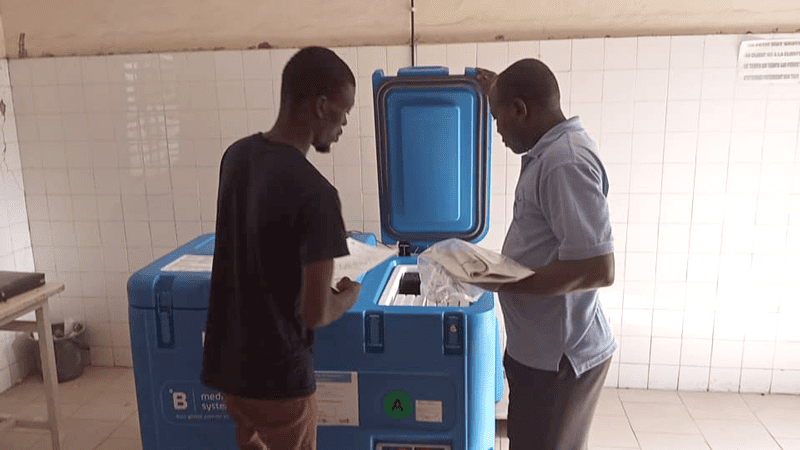

The medical clinic solar refrigeration project will further improve health. It is difficult to store refrigerated vaccines in unelectrified areas, which are often the same places where the target population is dispersed and hard to reach. Right now, only 58 percent of Benin’s children are “fully immunized,” meaning they have received eight shots against six diseases by their first birthdays. In comparison, American children are recommended to receive 17 shots against ten diseases by age one.

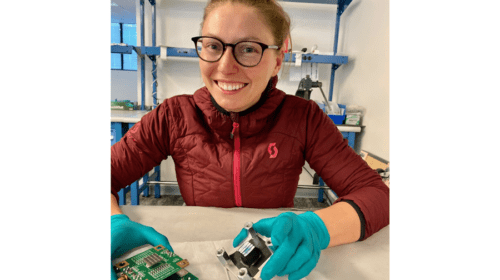

SELF chose “direct drive” solar refrigeration systems, coupled with extremely high-quality insulation to keep vaccines cold even when the panels were not providing energy.

“Solar appliances are only as strong as their weakest link,” says Jean-Baptiste Certain, SELF project manager. “Batteries are often the first point of failure for systems like these. By leveraging direct-drive technology, we can greatly improve reliability, and that reliability saves lives.”

During the day, the direct-drive system diverts surplus energy to a charging station. Using an Energy Harvest Control, clinic staff can plug in devices like cell phones or battery-operated lights and keep them ready for use. In addition, solar-powered streetlights were installed to illuminate the path to the clinics in the evening.

The SELF project received funding from the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), a U.S. foreign assistance entity created by Congress in 2004. “The Millennium Challenge Corporation invests in country-led solutions that reduce poverty and foster economic growth,” says Jason Bauer, director of finance, investment and trade. “This investment helps address health constraints that bind economic growth for thousands of people in the Kalalé District.” SELF and MCC worked in collaboration with MCC’s counterpart in Benin, the Millennium Challenge Account.

This successful solar project is bringing water – nim, in the local language – and gorudubu (joy) to an especially remote part of Benin. Koulou Démon, a Kalalé District resident said, “We are praying for other communities to get the same system.”

Could YOU Do It?

Readers – Could you live on one bathtub of water per day? ENERGIES Magazine challenges you to fill a tub and use only this water for 24 hours for bathing, toilet flushing, cooking and drinking. Let us know!

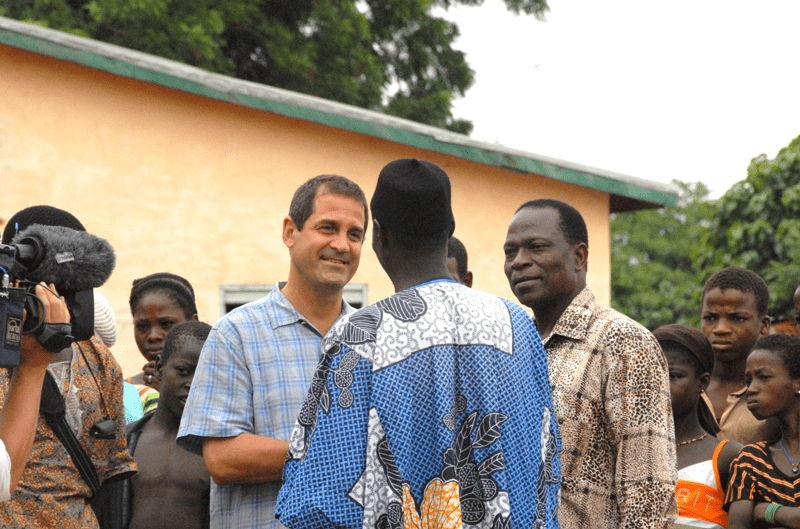

Headline Photo: SELF Executive Director Robert Freling in Benin. All photos courtesy of SELF.

Elizabeth Wilder is a freelance writer based in Houston, Texas.